CHAPTER 1: THE OPERATIONAL MODEL

Narrative: The Tent, The Truck, The Four Days

The archaeological tent appears on a Wednesday afternoon in late May. It’s a large white structure, perhaps forty meters by thirty, the kind you’d see at a major dig site. The accompanying signage is professionally printed: “Bodeminventarisatie – Archeologisch Onderzoek – Gemeente Vergunning #2024-AO-4472.” Nobody questions it. The Netherlands is lousy with archaeological significance, and construction projects routinely get delayed for months while someone carefully brushes dirt off Roman pottery shards.

Inside the tent, nothing happens for two days. A few people in hi-vis vests are seen entering and leaving. Clipboards. Measuring equipment. The performance of bureaucratic due diligence.

Thursday, 11 PM. The trucks arrive.

Not truck. Trucks, plural, but they move as one organism. The lead vehicle is something between a semi-trailer and a transformer: a specialized transport rig carrying what looks like an oversized industrial robot arm mounted on a tracked base. Behind it, three container trucks, their cargo anonymous behind corrugated steel. Behind those, two cement mixers, but not the rotating drum kind—these are something else, black matte finish, covered in sensors and what might be LiDAR arrays.

No workers emerge. No construction crew with thermoses and cigarettes and the usual banter. Instead, the lead truck’s sides unfold with hydraulic precision. The robot arm—no, robot arms, plural, there are three of them—power up with a rising electric whine that sounds expensive and foreign. Servos engage. The tracked base rolls backward off the truck bed under its own power.

By midnight, the tent is gone, packed away in minutes by the same mysterious efficiency. In its place, under the harsh glare of LED work lights running off the trucks’ generators, the foundation work begins.

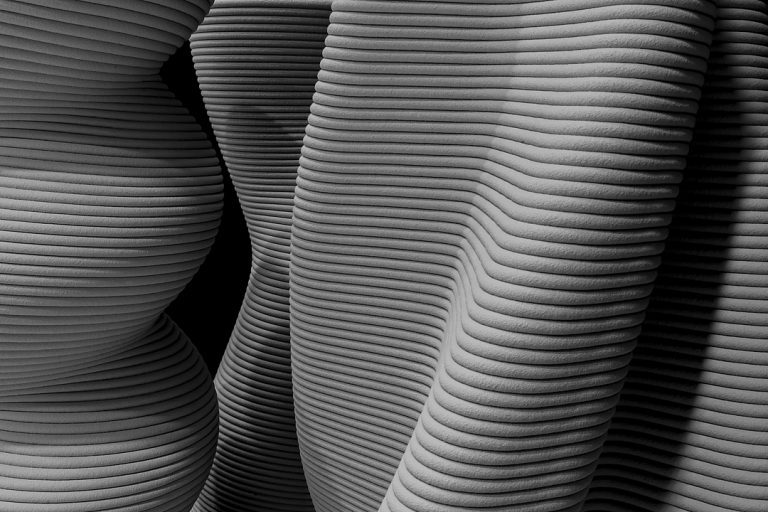

The tracked robot platform positions itself. Its arms extend, and what emerges is not a shovel but something that looks like a massive 3D printer nozzle. It begins depositing concrete in careful, geometrically perfect lines. Not pouring—depositing. Layer by layer, a foundation emerges from the printed concrete mix, darker than normal cement, almost black, with a matte finish that seems to absorb light.

By Friday morning, when the first commuters drive past on their way to work, six foundation slabs have been laid. Perfect rectangles, seventy-five square meters each, arranged in two rows of three with exactly four meters between them. The concrete is already load-bearing hard. Whatever is in that mix, it’s not standard C30/37 from the local batching plant.

Friday, the structures rise.

The robot platform moves to the first foundation. The nozzle adjusts, and it begins the vertical work. The walls appear not as poured forms but as deposited layers of that same black concrete, each layer perhaps two centimeters thick, each one hardening within minutes of deposition. The walls curve organically, not the hard right angles of traditional construction but flowing shapes that look almost grown rather than built. Steel reinforcement feeds from a separate spool, woven into the wall structure as it rises, a continuous process of concrete and steel becoming one material.

By Friday evening, four walls per structure, each two meters forty high. Windows and door frames are not cut afterward but formed during the printing process, the robot arms maintaining perfect voids where openings are specified. The structures begin to look like houses, though unlike any houses in the neighborhood. They look almost alien—organic, smooth, with none of the visible seams and joints of traditional construction.

Saturday morning, the roof work begins. More of the black concrete, but thicker layers now, reinforced with a visible lattice of steel. The roofs are not flat but gently domed, optimized for water runoff and structural integrity. By Saturday evening, six weather-tight structures stand where on Wednesday there was only grass and archaeological theater.

Sunday is systems day. The second robot platform emerges from another truck, smaller, more articulated, bristling with different tools. Electrical conduits are pulled through pre-printed channels in the walls. Plumbing lines, PEX not copper, snake through floor channels. HVAC units—mini-split heat pumps, two per house—are mounted on exterior walls by robot arms that work with millimeter precision. Solar panels, black to match the concrete, are installed on the roofs by a drone that lands, attaches, takes off, returns with another panel. Forty-two solar panels across six houses in three hours.

Monday morning, the finishing crews arrive. These are the only humans in the process, and there are eight of them total for all six houses. They install the prefabricated bathroom pods that arrived in the container trucks—complete units, shipped from China, sink and toilet and shower all in one six-hundred-kilogram fiberglass module that slots into place like a Lego brick. Kitchen units the same way: prefab counters, prefab cabinets, everything on wheels until the final installation. Interior doors on hinges. Flooring is already done—the printed concrete, polished to a smooth finish that looks almost like terrazzo.

By Monday evening, the workers leave. By Tuesday morning, the first families arrive.

They pull up in moving vans, cars packed with belongings, children pointing excitedly at their new homes. The houses have addresses now, printed on temporary signs: Nieuwe Weideweg 147A through 147F. Keys are distributed—digital keys, actually, smartphone-controlled locks that were programmed on-site. Furniture goes in. Curtains go up. By Tuesday evening, smoke rises from six chimneys that don’t exist because these are all-electric houses, but the metaphor stands: people are cooking dinner in homes that didn’t exist ninety-six hours ago.

Wednesday morning, exactly one week after the archaeological tent appeared, children are waiting for the school bus at the end of Nieuwe Weideweg. Six families, twenty-three people total, living in houses that materialized faster than traditional construction could pour a foundation.

Thursday morning, the gemeente receives six applications for address registration.

Friday afternoon, a building inspector named Henk van der Berg drives past Nieuwe Weideweg on his regular patrol route and nearly drives into a ditch.

INTERLUDE 1: THE ECONOMICS OF SPEED

Theory: How €28,000 Became Possible

Let’s dismantle the cost structure of traditional Dutch housing construction and compare it to what just happened on Nieuwe Weideweg. This isn’t magic. It’s industrial efficiency applied to a sector that has successfully resisted industrialization for a century.

Traditional Construction Timeline and Costs (75m² house):

The traditional model assumes you already own land. The gemeente has approved your permit after an eight-month review process. You’ve hired an architect who charged you twelve thousand euros to draw plans that mostly comply with building codes, with another four thousand in revision fees when the gemeente requested changes. You’ve paid eight thousand in permit fees and another six thousand in connection fees for utilities. You’re twenty-six weeks and thirty thousand euros in before a single shovel hits dirt.

Now construction begins. A foundation contractor arrives with a crew of four, works for a week, and charges sixteen thousand euros—eight thousand for materials, eight thousand for labor. The foundation must cure for a minimum of three weeks before structural work begins. You’re at week twenty-nine now.

Framers arrive. They construct the house skeleton from dimensional lumber—walls, roof trusses, interior framing. This is a three-week process with a crew of five skilled carpenters. Cost: forty-two thousand euros, roughly split between materials and labor. You’re at week thirty-two, and the house is still just wood bones.

Now the parade begins. Roofers (two weeks, twelve thousand). Exterior contractors for brick facades or other cladding (three weeks, twenty-eight thousand). Window and door installation (one week, fifteen thousand). Then the interior trades: electricians (two weeks, fourteen thousand), plumbers (two weeks, sixteen thousand), HVAC specialists (one week, eleven thousand), insulation contractors (one week, eight thousand), drywall installers (two weeks, twelve thousand), flooring specialists (one week, nine thousand), painters (one week, seven thousand), kitchen installers (one week, fourteen thousand), bathroom fitters (one week, nine thousand).

Each trade must be scheduled sequentially or with careful coordination. Each trade includes travel time, setup time, and the inherent inefficiency of human labor—coffee breaks, mistakes, rework, personality conflicts, the reality that Frans called in sick and now the plumbing is delayed three days.

Total timeline from permit approval to move-in: thirty-eight to forty-four weeks. Total construction cost excluding land: two hundred twenty thousand euros for a seventy-five square meter house. Of this, approximately forty-two percent is direct labor costs—roughly ninety-two thousand euros paid to human beings for their time and skill.

The Guerrilla Construction Model:

Start time: Wednesday evening, 11 PM. End time: Tuesday morning, 6 AM. Elapsed time: ninety-six hours. Six houses completed simultaneously.

Equipment Costs (Amortized):

The lead robot platform is custom-manufactured in Shenzhen by a company that normally produces industrial automation for automotive factories. Purchase price: one hundred forty thousand euros per unit. Expected operational lifespan: one thousand houses before major maintenance. Amortized cost per house: one hundred forty euros.

The secondary systems-installation robot: eighty thousand euros, one thousand house lifespan, eighty euros per house.

The concrete mixing and pumping system: sixty thousand euros, fifteen hundred house lifespan, forty euros per house.

The autonomous delivery trucks (three vehicles): one hundred eighty thousand total, amortized over ten thousand deliveries, eighteen euros per house.

Total equipment amortization: two hundred seventy-eight euros per house.

This seems impossibly low until you understand the model. Guerrilla Construction owns thirty robot platforms. They’re building six hundred houses per year. The equipment never sits idle—it moves from site to site on a continuous rotation, three to four days per site, then immediately transported to the next location. The entire capital investment of eight point four million euros in robotics is generating value three hundred days per year.

Labor Costs:

Robot operation and oversight: two technicians per site, four days per site, at one hundred twenty euros per technician-day. Total: nine hundred sixty euros across six houses, or one hundred sixty euros per house.

Finishing crew: eight workers for one day at one hundred fifty euros per worker-day. Total: one thousand two hundred euros across six houses, or two hundred euros per house.

Total direct labor per house: three hundred sixty euros.

Compare this to the ninety-two thousand euros in traditional construction. The labor cost reduction is ninety-nine point six percent. This is not a typo. This is industrial automation applied to construction.

Materials Costs:

The black concrete mix is proprietary but not exotic. It’s based on standard Portland cement with graphene oxide additives that accelerate curing time and increase compressive strength. The formula was developed by a materials science team at Tsinghua University and licensed to Guerrilla Construction for eighty thousand euros per year. At six hundred houses per year, that’s one hundred thirty-three euros per house in licensing fees.

Raw materials per house: cement, aggregates, graphene additives, water: two thousand eight hundred euros. Steel reinforcement, pre-cut to specification in China: one thousand four hundred euros. This is delivered in numbered bundles—the robot knows to use bundle 1A for the north wall, bundle 1B for the south wall. Zero cutting waste, zero measurement errors.

Prefab bathroom pod from Guangdong: one thousand eight hundred euros, delivered to Rotterdam. This is a complete bathroom—shower tray, wall panels, toilet, sink, mirror, lighting, exhaust fan, all wiring and plumbing pre-installed. It arrives in a crate. The finishing crew wheels it into position, connects two water lines, one drain line, and one electrical connection. Installation time: forty-five minutes. Compare this to traditional bathroom construction: two weeks, nine thousand euros.

Prefab kitchen from the same manufacturer: one thousand two hundred euros. Countertop, cabinets, sink, all pre-assembled. Installation time: thirty minutes.

Windows and door units: two thousand four hundred euros total per house for three windows (double-glazed, tilt-turn, German manufacture) and two doors (exterior steel-core, interior hollow-core). These are standard catalog items, ordered in bulk at volume discounts.

Electrical system: pre-wired panel from China (four hundred euros), conduit and wire (three hundred euros), fixtures and outlets (two hundred euros), installation labor already counted above. Total: nine hundred euros.

Plumbing: PEX tubing (two hundred euros), fixtures (four hundred euros), installation labor already counted. Total: six hundred euros.

HVAC: two mini-split heat pump units, Chinese manufacture, twenty-five hundred euros total. Installation by robot: no additional cost.

Solar panels: five kilowatts, Chinese panels, three thousand euros including mounting hardware and inverter.

Insulation: spray foam, applied by robot nozzle during wall printing, eight hundred euros in materials.

Flooring: the printed concrete is the floor. Polishing compound: two hundred euros.

Interior finishing: paint (three hundred euros), door hardware (one hundred euros), miscellaneous (two hundred euros).

Total materials cost per house: nineteen thousand eight hundred euros.

Overhead and Administrative:

Site preparation—basic grading, utility connections to property line: two thousand euros per house.

Transportation of materials and equipment to site: four hundred euros per house.

Insurance during construction: three hundred euros per house.

Legal and administrative costs (permit applications, legal representation): one thousand five hundred euros per house.

Contingency (five percent of total): one thousand two hundred euros per house.

Total overhead: five thousand four hundred euros per house.

Grand total per house: twenty-five thousand eight hundred thirty-eight euros.

Let’s round it to twenty-eight thousand to include some buffer. This is an eighty-seven point three percent reduction compared to traditional construction costs.

The Timeline Economics:

Traditional construction timeline: thirty-eight weeks means thirty-eight weeks of financing costs if you’re borrowing money for construction. At four percent interest on two hundred thousand euros, that’s roughly six thousand euros in interest charges. Guerrilla Construction timeline: ninety-six hours means effectively zero financing costs.

Traditional construction timeline: thirty-eight weeks of coordination overhead, project management fees (typically eight to twelve percent of construction costs), roughly twenty thousand euros. Guerrilla Construction: four days, minimal coordination needed, management costs included in the overhead already calculated.

Traditional construction: weather delays, material delivery delays, labor availability issues, inspection scheduling delays. Average project runs fourteen percent over timeline, meaning forty-three weeks and additional costs. Guerrilla Construction: weather-resistant robotic operation (they work in rain, snow, night), no labor scheduling conflicts (robots don’t call in sick), no material delivery delays (everything arrives in the initial trucks), no inspection scheduling issues (everything is documented with continuous video and sensor data).

The Scaling Economics:

Everything described above assumes a production rate of six hundred houses per year. But the model is designed to scale. At one thousand houses per year, the equipment amortization drops to one hundred sixty-seven euros per house. Material costs drop further through bulk purchasing—at one thousand houses per year, Guerrilla Construction is purchasing twelve thousand cubic meters of concrete materials, six hundred bathroom pods, six hundred kitchen units. The volume discounts are enormous.

At two thousand houses per year, the model reaches twenty-four thousand euros per house. At five thousand houses per year—achievable with one hundred robot platforms operating continuously—the cost drops below twenty-two thousand euros per house.

This is the economics of true industrialization. This is what happens when you apply automotive manufacturing principles to housing construction. This is what the traditional construction industry has successfully prevented for decades through regulatory capture and guild-like control of skilled trades.

And this is why Gemeente Inspector Henk van der Berg is about to have a very difficult week.

CHAPTER 2: THE CASCADE

Narrative: When Six Becomes Sixty Becomes Six Hundred

Henk van der Berg stands at the end of Nieuwe Weideweg, coffee cooling in his hand, trying to understand what he’s seeing. The houses are real. They’re occupied. There are children playing in what might generously be called yards but are really just patches of dirt where grass will presumably be planted.

He calls his supervisor. “Gerda, we have a situation.”

Within ninety minutes, three gemeente officials are on-site. They knock on doors. The families are cooperative, even friendly. Yes, they own the land—here are the deeds, purchased three months ago from a farmer who sold off a corner of his property. Yes, they know they need building permits. No, they didn’t get them in advance. Yes, they understand this is irregular. Here is the contact information for their legal representation.

The legal representation is a firm out of Rotterdam called Velsing & Partners. When Gerda calls them, she gets a junior associate named Daan who sounds like he’s been waiting for this call and is possibly enjoying it.

“Yes, my clients are aware they constructed prior to permit approval. They’re prepared to pay any reasonable fines. However, I’d like to direct your attention to Article 2.27 of the Omgevingswet. The structures are demonstrably safe—we have complete structural engineering reports from Bureau Veritas. They meet or exceed all relevant building codes. My clients have families, including seven children under the age of twelve. Any action requiring demolition or evacuation would need to pass a proportionality test under both national law and the European Convention on Human Rights, Article Eight. We’re prepared to litigate this to Strasbourg if necessary, though we’d prefer a more cooperative approach.”

This is not what gemeente building inspectors are used to hearing. Usually, people who build without permits are embarrassed, apologetic, trying to fly under the radar. These people have structural engineering reports from Bureau Veritas, one of the most respected certification bodies in Europe. They have lawyers who casually reference Strasbourg.

Gerda schedules a full inspection for the following week. When the building inspectors arrive—there are four of them, because this is unusual enough to warrant a team—they find something deeply frustrating: the houses are well-built. Annoyingly well-built. The walls are plumb to within two millimeters. The electrical work is textbook-perfect. The plumbing shows no leaks under pressure testing. The structural integrity is excellent—the inspection team actually calls in an external structural engineer who spends three hours examining one house and concludes that it would probably survive a significant earthquake, which is irrelevant in the Netherlands but speaks to the over-engineering.

They find minor violations. A handrail height is thirty centimeters too low on one set of interior stairs. Some electrical outlets are five centimeters off the standard height. The gemeente issues a violation notice requiring corrections. Estimated cost to fix: eight hundred euros per house.

Gerda thinks this is over. She’s wrong.

Three weeks later, a gemeente in Gelderland receives address registration applications for twelve houses on Bosrandweg. The inspector who drives out finds twelve occupied homes that weren’t there a month ago. Same black concrete. Same organic curves. Same impossible construction speed.

The week after, Overijssel: eighteen houses.

The week after that, Noord-Brabant: nine houses.

Then Friesland: fifteen houses.

Then Limburg: twenty-four houses.

By July, three months after Nieuwe Weideweg, Guerrilla Construction—because they’re not hiding anymore, the name appears on the legal filings—has completed one hundred sixty-three houses across twelve gemeentes in seven provinces.

The pattern is always the same. Land is purchased legally, often agricultural land on the edge of existing developments. The archaeological tent appears. The robots arrive. Four days later, families move in. Then the gemeente is notified.

In some gemeentes, officials attempt to issue stop-work orders, but the work is already done. Some attempt to deny address registrations, but families are already living there, children are already enrolled in local schools, and the optics of making children homeless over permit technicalities are politically untenable.

Some gemeentes try to issue demolition orders. These immediately face legal challenges. The cases are tied up in court for months. During those months, the families keep living there. The houses acquire legitimacy through occupancy—how do you demolish a home where a three-year-old has birthday parties?

A few gemeentes try a softer approach. They negotiate. The gemeente in Drenthe works out an agreement: pay fifteen thousand euros in retroactive permit fees per house, make some minor corrections, and they’ll grant permits. Guerrilla Construction agrees. The houses are legalized.

This creates a precedent. Other gemeentes start negotiating rather than fighting. The fees vary—some charge twenty thousand, some charge ten thousand, one gemeente in Groningen charges only five thousand because the local council is desperate to increase housing stock and views Guerrilla Construction as solving their problem for them.

By September, Guerrilla Construction has completed three hundred forty houses. They’re building faster now—the robot crews are more efficient with experience, the supply chain is optimized, they’ve learned which gemeentes are cooperative and which are hostile.

In October, the Telegraaf runs a major feature story. “The Housing Revolution You Haven’t Heard About: How One Company is Building Homes for €28,000.” The article includes interviews with families, cost breakdowns, and a particularly damning comparison of a Guerrilla Construction house versus a similar-sized traditional new-build in the same gemeente: twenty-eight thousand versus two hundred sixty thousand euros.

The article goes viral. The waiting list for Guerrilla Construction houses grows from forty families to eight hundred families in two weeks.

In November, a collective of traditional construction companies files a lawsuit. They’re suing the gemeente of Drenthe for illegally approving the Guerrilla Construction homes. The legal theory is that the gemeente violated proper permit processes and created unfair competitive advantage.

The lawsuit names Guerrilla Construction as a co-defendant.

The war is now formal.

INTERLUDE 2: THE REGULATORY CAPTURE SYSTEM

Theory: How Housing Became A Protection Racket

Let’s be precise about what’s actually happening in the Dutch housing market, because the situation described above—traditional construction companies suing to stop cheaper housing—seems insane until you understand that the entire system is designed to extract maximum rent from the fundamental human need for shelter.

The Land Monopoly:

The Netherlands has thirty-three thousand six hundred eighty-eight square kilometers of land area. Of this, approximately seventeen percent is developed as residential, commercial, or industrial land. Another twenty-four percent is agricultural. The remaining fifty-nine percent is forests, nature reserves, water bodies, and infrastructure.

So there’s land. The scarcity is artificial.

Dutch land use policy since the post-war reconstruction era has been based on a model of controlled densification. Gemeentes have near-total power over land designation through bestemmingsplannen (zoning plans). Land designated as agricultural cannot be built on for residential purposes. Land designated as residential can be built on, but only after gemeente approval, only according to gemeente-specified densities, and only by approved developers who have often made arrangements with the gemeente years in advance.

This creates an artificial bottleneck. The gemeente controls supply. Developers must negotiate with the gemeente for land release. The gemeente has every incentive to release land slowly, because rapid supply increases would crash housing prices, which would anger existing homeowners, who vote.

Result: Land that should cost perhaps fifty euros per square meter (its agricultural value) instead costs three hundred to five hundred euros per square meter in urban areas, two thousand euros per square meter in Amsterdam. This is a markup of four hundred to three thousand percent based purely on bureaucratic designation change.

The Permit Cartel:

Traditional construction companies have had decades to optimize for the permit system. They employ specialists who know exactly which gemeente officials to schmooze, exactly which architectural features will pass the welstandscommissie (aesthetic committee) review, exactly how to navigate the Byzantine environmental impact requirements.

Small developers and individual builders cannot compete. The knowledge barrier is too high, the process too opaque. This entrenches the existing large construction firms.

The permit process itself is explicitly designed to be slow. The average time from application to approval for a small residential project is eight months. For larger projects, it’s often two years. This isn’t because the reviews are technically complex—a competent structural engineer can review residential plans in three days. It’s slow because gemeente planning departments are understaffed by design, because the review process includes multiple discretionary approval stages, and because any neighbor can file an objection that triggers additional review periods.

This delay is worth money to incumbent developers. If you’re a large construction firm with ten projects in the pipeline, the eight-month delay on each one doesn’t hurt you—you’re always building something. But if you’re a new entrant trying to build one project, eight months of carrying costs on land you’ve already purchased can destroy your finances.

Result: Market consolidation. Five large construction companies control forty-three percent of new residential construction in the Netherlands. They don’t compete on price; they compete on gemeente relationships.

The Trade Guilds:

Dutch construction relies on specialized trades, each with its own certification requirements. You cannot legally perform electrical work on a residence without holding specific certifications. Same for plumbing, gas fitting, structural work, and various other specialties.

These certifications require years of apprenticeship and formal education. They’re defended as safety measures, and there’s some truth to that—you don’t want unqualified people wiring houses. But they also function as barriers to entry that restrict labor supply and keep wages high.

The average Dutch electrician earns fifty-five thousand euros per year. This is nearly double what electricians earn in Poland or Romania. The skill required is identical. The productivity is nearly identical. The wage difference exists because certification rules prevent Romanian electricians from working in the Netherlands without going through years of additional Dutch-specific credentialing.

This isn’t about safety. It’s about protecting domestic labor from competition.

Result: Construction labor costs in the Netherlands are among the highest in Europe—forty-eight euros per hour average versus twenty-two euros in Poland. This premium flows directly to tradespersons and their guilds but makes housing construction dramatically more expensive.

The Materials Markup:

Netherlands has relatively few domestic manufacturers of construction materials. Most materials are imported from Germany, Belgium, or China. But they’re not imported directly to construction sites. They flow through distribution networks—wholesalers who purchase from manufacturers and sell to contractors.

These distributors add markups of twenty to forty percent. A window unit that costs one hundred twenty euros to manufacture in Germany sells to a Dutch distributor for one hundred thirty euros (small manufacturer markup) and then sells to a contractor for one hundred eighty euros (thirty-eight percent distributor markup).

Why don’t contractors buy directly from manufacturers? Some large ones do, but most can’t because manufacturers require minimum order volumes that small contractors can’t meet. And manufacturers prefer selling to distributors anyway—it’s simpler to sell in bulk to five distributors than to invoice fifty small contractors.

Result: Materials costs in Dutch construction are inflated by twenty-five to forty percent compared to what bulk direct purchasing would cost.

The Banking Extraction:

The average Dutch residential mortgage is three hundred fifty thousand euros at current property prices. With a typical mortgage rate of four percent over thirty years, the total interest paid is approximately two hundred thirty thousand euros.

Think about that. A house that costs perhaps one hundred fifty thousand euros in materials and labor to build (using traditional methods) sells for three hundred fifty thousand euros. The buyer then pays two hundred thirty thousand in interest to the bank. The total cost of homeownership: five hundred eighty thousand euros. Of this, forty percent is interest paid to banks.

Banks have enormous incentive to keep housing prices high because higher prices mean larger loans mean more interest income. Banks oppose anything that would dramatically reduce housing costs because it threatens their business model.

When Guerrilla Construction started offering houses for twenty-eight thousand euros, they explicitly avoided mortgage financing. Buyers pay cash or use peer-to-peer lending. This cuts banks out entirely.

Result: Banks are now lobbying gemeentes and national government to regulate Guerrilla Construction out of existence. They’re funding “studies” that raise safety concerns. They’re threatening to blacklist any gemeente that approves Guerrilla projects by refusing to issue mortgages in those areas.

The Speculation Economy:

Dutch housing has become an investment vehicle. Approximately thirty-two percent of residential property in the Netherlands is owned by investors, not owner-occupants. These investors—ranging from small-time landlords to massive institutional funds—purchase property for rental income and capital appreciation.

This investor demand competes with homebuyer demand, driving up prices. And investors can outbid individual buyers because they’re purchasing with cash or accessing commercial lending at better rates than residential mortgages.

Result: Housing prices are decoupled from construction costs or wage affordability. Prices reflect what investors are willing to pay for yield and appreciation, not what houses cost to build or what families can afford. The median Dutch household income is forty-four thousand euros. The median house price is four hundred thirty thousand euros—a multiple of 9.8. Historically, the sustainable multiple was 3.0 to 4.0.

The Protection Racket:

Here’s what the lawsuit against Drenthe gemeente is really about. Traditional construction companies aren’t suing because Guerrilla Construction builds unsafe houses—the houses pass inspection. They’re not suing because Guerrilla Construction is breaking laws—the gemeente approved the permits.

They’re suing because Guerrilla Construction is revealing that the emperor has no clothes.

If houses can be built safely and legally for twenty-eight thousand euros, why are traditional construction companies charging two hundred fifty thousand? The answer is: Because they can. Because the system protects them. Because gemeentes slow-walk permits for anyone who doesn’t play the game. Because banks won’t finance non-traditional construction. Because distributors won’t sell materials in bulk to outsiders. Because trade guilds restrict labor supply.

Guerrilla Construction bypassed every single control point. They use robots instead of guild labor. They buy materials directly from China in bulk. They build first and get permits second, removing the gemeente’s timeline leverage. They don’t need bank financing. They documented everything so thoroughly that safety objections are baseless.

And traditional construction companies are suing because if this model succeeds, their entire extraction system collapses.

The lawsuit claims “unfair competitive advantage.” The reality: Guerrilla Construction is competing fairly for the first time in decades. The existing system was unfair—designed to protect incumbents from competition. Guerrilla Construction is actual competition, and the incumbents are discovering they can’t compete.

This is what regulatory capture looks like when it’s threatened. The captured regulators and the incumbent firms turn to courts to defend their monopoly because they’ve lost the ability to compete on price, quality, or efficiency.

The lawsuit will fail, but not before Guerrilla Construction spends two hundred thousand euros on legal defense. That’s the point. The process is the punishment. Drive up their costs. Slow them down. Signal to anyone else thinking of disrupting the system: We’ll make you pay for it.

But here’s the thing about revolutions: They don’t need permission.

And three hundred forty families in three hundred forty Guerrilla Construction houses don’t care about the lawsuit. They’re living in homes they own outright, with no mortgage debt, in houses that cost less than a new car.

That’s a fact on the ground that no lawsuit can bulldoze.

CHAPTER 3: THE HOUSES THEMSELVES

Narrative: What €28,000 Actually Buys

Lisa Vermeulen walks through her house for the first time with her eight-year-old daughter, Emma. They’re in Nunspeet, Gelderland, one of the eighteen-house cluster that went up in four days in early June. Lisa sold her apartment in Utrecht—a cramped fifty-square-meter place that cost her three hundred twenty thousand euros three years ago—and netted two hundred ninety thousand after paying off her mortgage. She paid twenty-eight thousand cash for this house. The remaining two hundred sixty-two thousand euros sits in her savings account like a psychological cushion she’s never had before.

“It feels weird,” Emma says, running her hand along the wall. The black concrete is smooth, almost warm to the touch despite being concrete. “Like we’re inside a sculpture.”

She’s not wrong. The walls curve gently, no hard right angles except where necessary for door frames. The living room flows into the kitchen area without a clear boundary—the space is open, sixty square meters of uninterrupted flow. The ceiling follows the roofline, gently domed, three meters high at the center, two and a half at the edges. It makes the space feel larger than it is.

The windows are triple-glazed, tilt-turn German units that cost more per window than some entire window walls in traditional construction. But at bulk pricing, ordered by the thousands, Guerrilla Construction pays one hundred forty euros per window. They installed three: one large one in the living area, two smaller ones in the bedroom and bathroom. The light is good—the windows face south and west, designed that way by the AI that planned the site layout to optimize for solar gain in winter and natural light year-round.

The floor is the printed concrete, polished to a satin finish and sealed. It looks like terrazzo—smooth, slightly mottled, the graphene additives creating subtle dark swirls in the surface. It’s radiant-heated from embedded PEX tubing laid during the printing process. The heating is electric, powered by the solar panels on the roof and a small battery system in the utility closet.

“Where are all the… things?” Emma asks. “The radiators and stuff?”

“In the walls,” Lisa says, though she’s not entirely sure herself. The house is so clean of the usual visual noise of building services. No visible ducts, no radiators, no exposed pipes. Everything is embedded in the structure itself. The electrical outlets are flush-mounted, barely visible. The lighting is LED strips embedded in ceiling channels, indirect and pleasant.

The bathroom is a six-square-meter pod, prefabricated in China and installed as a complete unit. Emma opens the door and gasps. “It’s like a spaceship!”

The walls are smooth fiberglass, slightly curved, white with gray accents. The shower is a corner unit with a rainfall head and a handheld attachment. The toilet is wall-mounted, with a concealed tank. The sink is integrated into a small counter, with storage underneath. A mirror fills most of one wall, backlit with LEDs. The whole thing feels futuristic, seamless, nothing like the tiled bathrooms of traditional Dutch houses with their grouted seams and eventual mold problems.

The kitchen is similarly prefabricated—three meters of counter space with integrated sink, a two-burner induction cooktop, space for a small fridge underneath, cabinets above and below. It’s IKEA-grade, nothing fancy, but it’s functional and clean. Lisa plans to upgrade it eventually, but for now, it’s perfectly adequate for a household of two.

The bedroom is upstairs—a sleeping loft, really, accessible by a steel staircase that’s more ladder than stairs. It’s cozy up there, perhaps fifteen square meters, with one of the windows looking out over the farmland that surrounds the development. Emma has already claimed it. Lisa will sleep on the fold-out sofa bed in the living area. It’s not ideal, but it’s temporary—she’s already talking to Guerrilla Construction about a twenty-square-meter addition next year. Estimated cost: eight thousand euros.

What strikes Lisa most is the silence. The concrete walls are thick—twenty-five centimeters—and the density of the material provides excellent sound insulation. She can’t hear her neighbors at all, even though the houses are only four meters apart. The HVAC system is whisper-quiet, just a barely perceptible hum when it kicks on. There’s no creaking, no settling noises that old houses make. The structure is monolithic, printed in one continuous process, so there are no joints to shift and creak.

The air quality is strange in a good way. The house is so tightly sealed—modern passive-house tight—that it requires mechanical ventilation. The HVAC system includes an energy recovery ventilator that brings in fresh air while capturing heat from the exhaust air. The result is that the air feels fresher than in her old apartment, never stuffy, but also never drafty.

Emma runs upstairs and down three times, testing the space. “Can I paint my room?” she asks.

“It’s not really a room, it’s a loft,” Lisa says. “But yes, we can paint it.”

“Can we paint it purple?”

Lisa looks at the smooth black concrete walls and tries to imagine them purple. “We’ll start with white primer and see how we feel after that.”

That evening, they eat dinner at a folding table—their furniture hasn’t arrived yet. Lisa looks around the space and does a mental calculation she’s done a dozen times since signing the purchase agreement. Her old apartment cost her fourteen hundred euros per month in mortgage payments. This house costs her nothing except utilities and the eight hundred euro annual insurance premium. Her monthly housing cost dropped from fourteen hundred euros to approximately two hundred fifty euros for utilities and sixty-seven euros for insurance.

Monthly savings: one thousand eighty-three euros.

Annual savings: twelve thousand nine hundred ninety-six euros.

In twenty years, assuming she just saved that money at a conservative four percent return, she’d have four hundred thousand euros. More than the entire price of her old apartment.

This is what twenty-eight thousand euros bought her: Financial breathing room for the rest of her life.

Two houses down, Marcus and Petra Hoffman are having a different experience. They’re in their late thirties with three kids—ages six, nine, and eleven. They bought a ninety-square-meter Guerrilla Construction house, the larger model, which cost thirty-four thousand euros. It has two bedrooms upstairs, a bathroom on each floor, and a slightly larger kitchen.

Marcus is a software engineer who works remotely. Petra is a teacher. Together they gross seventy-two thousand euros per year. In their previous life, they rented a three-bedroom house in Amersfoort for nineteen hundred euros per month. They saved for six years to accumulate the thirty-four thousand for this house. They had been saving for a down payment on a traditional house, hoping to buy something in the two hundred fifty thousand euro range, but the market kept rising faster than they could save.

When they heard about Guerrilla Construction, Marcus thought it was a scam. “Houses don’t cost thirty thousand euros,” he said. “It’s impossible.”

Petra made him go look at one of the early developments in Drenthe. They walked through a house with the family who lived there. It was real. It was solid. It was weird-looking but functionally excellent.

They bought land—agricultural land on the edge of Nunspeet that was being sold off by a retiring farmer. Seven hundred fifty square meters for forty-eight thousand euros. With the house, their total cost was eighty-two thousand euros.

Their previous landlord sold the house they’d been renting for three hundred eighty thousand euros to an investor who plans to rent it for twenty-two hundred euros per month.

Marcus and Petra now own their home outright. No mortgage. No landlord. Their monthly housing cost: utilities, insurance, and property tax, totaling approximately four hundred euros.

They’re saving fourteen hundred euros per month compared to renting.

“I keep waiting for the catch,” Petra says, sitting in their living room on their second evening in the house. “Like we’re going to find out it’s made of toxic materials or it’s going to collapse or something.”

Marcus has already researched this obsessively. He’s read the structural engineering reports, the materials safety data sheets, the building code compliance documents. “It’s solid,” he says. “The concrete is stronger than normal residential concrete. The steel reinforcement is more dense than code requires. If anything, it’s over-engineered.”

“Then why isn’t everyone doing this?”

“Because until now, no one could. The robots are new. The concrete formulation is new. The whole process is new. Guerrilla Construction figured out how to automate what used to require thirty different specialized trades.”

Their eleven-year-old daughter, Sophie, comes downstairs from the loft bedrooms. “I can hear Luuk snoring from my room,” she complains. Luuk is her six-year-old brother.

“Then close your door,” Petra says.

“I did. I can still hear him.”

This is the one acoustic flaw Marcus has noticed. The bedrooms upstairs are separated by non-structural partition walls that were printed during the main construction process, but they’re only ten centimeters thick. Sound transfers between rooms more than it should. It’s not terrible, but it’s noticeable.

He makes a note to ask Guerrilla Construction about it. He’s already part of an online forum of Guerrilla Construction homeowners—there are three hundred forty families now, and they’ve organized themselves into a remarkably active community. They share tips, modifications, complaints, and solutions. Someone in Friesland posted a method for adding additional sound insulation to the partition walls: acoustic panels from IKEA, mounted on the walls with adhesive. Cost: one hundred twenty euros per room. Installation time: two hours.

This is what the houses are: Functional, efficient, slightly imperfect, and radically affordable. They’re not luxury housing. They’re not trying to be. They’re trying to be good enough housing at a price that allows normal families to own rather than rent, to build wealth rather than transfer it to landlords and banks.

And for three hundred forty families across the Netherlands, they’re working.

INTERLUDE 3: THE TECHNICAL REVOLUTION

Theory: AI, Standardization, and the Death of Artisanal Construction

Let’s deconstruct exactly how Guerrilla Construction achieved what traditional construction claims is impossible. This isn’t magic. It’s the application of manufacturing principles that have been standard in other industries for decades but have been systematically excluded from residential construction.

The AI Planning System:

Every Guerrilla Construction site begins with an AI planning session. The process takes approximately four hours and costs effectively zero in marginal costs—the AI system has already been developed, and running it costs only computation time.

Input data:

- Plot dimensions and boundaries (from cadastral surveys)

- Soil composition data (from geological surveys, publicly available)

- Local climate data (solar angles, prevailing winds, average temperatures)

- Utility connection points (water, sewer, electrical, internet)

- Gemeente building requirements (setbacks, height limits, coverage ratios)

- Number of houses to be built on the plot

- House models selected by buyers (sixty, seventy-five, or ninety square meter options)

The AI—a specialized neural network trained on ten thousand residential construction projects—generates an optimal site plan. It determines:

- Exact placement of each house to maximize solar gain

- Orientation of each house to optimize natural light and minimize heat loss

- Routing of shared utilities to minimize trenching costs

- Positioning of access roads and walkways

- Drainage patterns and water management

- Compliance with all local building codes

The output is a complete construction plan with millimeter precision. Every house location is specified with GPS coordinates. Every utility line is mapped. The system even generates the exact sequence in which houses should be printed to minimize equipment repositioning time.

This planning would take a human architect team approximately six weeks and cost twelve to fifteen thousand euros. The AI does it in four hours at near-zero cost.

More importantly, the AI optimizes in ways human planners can’t. It models thousands of potential configurations and selects the optimal one according to multi-variable optimization criteria: construction cost, energy efficiency, aesthetic harmony, construction time, and code compliance all weighted simultaneously.

The Standardization Philosophy:

Traditional residential construction treats every house as a unique project. Even tract housing developments that build identical-looking houses involve significant per-house customization in the construction process because each house is built by human tradespeople who introduce small variations.

Guerrilla Construction takes the opposite approach: Radical standardization.

There are three house models:

- Model A: Sixty square meters, one bedroom loft, one bathroom, €28,000

- Model B: Seventy-five square meters, one bedroom loft, one bathroom, larger living space, €30,000

- Model C: Ninety square meters, two bedroom lofts, two bathrooms, €34,000

Within each model, there are four window configurations (different arrangements of the three or four windows) and three door positions (front, side-left, side-right). This creates thirty-six total configurations across all models.

That’s it. Thirty-six options total. No custom sizing, no unique layouts, no “I want the kitchen on the other side” modifications. You select from thirty-six options.

This seems limiting until you understand the economic power it unleashes.

The Prefabrication Supply Chain:

Every component in a Guerrilla Construction house is manufactured in volume and standardized.

Bathroom pods: These are manufactured in Guangdong, China, by a company called Jiangsu Prefab Technology. Guerrilla Construction orders in batches of five hundred units. The manufacturer produces three models (corresponding to Models A, B, and C), and each model is identical down to the placement of every screw hole.

The pods are manufactured on an assembly line. Fiberglass shells are molded in large presses—six shells per day per press, three presses running continuously. Plumbing fixtures are installed by workers following a digital work instruction system that projects exactly where each component goes. Electrical wiring is pre-installed following a standard diagram. Quality control is automated—each pod passes through a test station that checks for water leaks, electrical continuity, and dimensional accuracy.

Cost per bathroom pod, ex-factory: one thousand two hundred euros. Shipping to Rotterdam in a forty-foot container (eight pods per container): three hundred euros per pod. Total delivered cost: one thousand five hundred euros.

Compare this to building a bathroom on-site in the traditional method: six square meters of tile work, two weeks of plumber time, electrician time, fixture costs, labor coordination. Traditional cost: eight to nine thousand euros. The prefab pod is eighty-three percent cheaper.

Kitchen units: Similar story. Manufactured in the same facility in Guangdong. Three models, all identical within each model. Cost ex-factory: eight hundred euros. Delivered to Rotterdam: one thousand euros. Traditional on-site kitchen for the same specification: six to seven thousand euros.

Window and door units: These are actually manufactured in Poland by a company called Drutex, one of Europe’s largest window manufacturers. Guerrilla Construction orders in batches of two thousand units. Because the sizes are standardized—only three window sizes and two door sizes across all models—Drutex can produce them on long production runs without retooling. This is wildly more efficient than custom windows.

Cost per window unit: one hundred twenty euros (compared to three hundred fifty to four hundred euros for custom residential windows). Cost per door: one hundred eighty euros (compared to five hundred to eight hundred euros).

Steel reinforcement: Manufactured in China, cut to exact specifications by automated cutting machines. Each bundle is numbered and corresponds to a specific location in a specific house model. The robot knows that bundle A1-N goes in the north wall of Model A houses. There’s zero measurement, zero cutting, zero waste on-site.

Concrete mix: This is where Guerrilla Construction actually innovates rather than just optimizing. The proprietary concrete formula was developed in partnership with Tsinghua University’s materials science department.

Standard concrete cures slowly—typically twenty-eight days to reach full strength, though it’s load-bearing after seven days. This is fine for traditional construction where you’re building one house over months, but it’s a bottleneck for rapid construction.

The Guerrilla Construction formula uses:

- Standard Portland cement

- Standard aggregates (sand and gravel)

- Graphene oxide nanoparticles (0.05% by weight)

- Proprietary accelerant compounds

- Carefully controlled water ratio

The graphene oxide serves two functions. First, it acts as a nucleation site for cement hydration, accelerating the curing process. Second, it increases the tensile strength of the concrete by creating a reinforcing network at the molecular level.

Result: The concrete reaches eighty percent of full strength in eighteen hours and full strength in seventy-two hours. This allows the robots to print a complete house structure in four days and have it be fully load-bearing immediately.

The compressive strength is forty-five megapascals (compared to thirty for standard residential concrete). The tensile strength is eight megapascals (compared to three for standard concrete). It’s significantly over-engineered for residential use, but the formula is optimized for manufacturability and consistency rather than minimum viable strength.

Cost per cubic meter of this special concrete mix: one hundred sixty euros (compared to eighty euros for standard concrete). But the speed advantage and strength advantage more than compensate for the material cost premium.

The Robotics System:

The primary construction robot is a mobile platform weighing eight thousand kilograms, measuring six meters long by three meters wide when deployed. It’s essentially an autonomous construction factory.

The base is a tracked platform similar to what’s used in military vehicles or large construction equipment. It can traverse rough terrain and position itself with centimeter accuracy using RTK GPS (real-time kinematic GPS, accurate to two centimeters).

Mounted on the platform are three robotic arms, each with six degrees of freedom. These are industrial robots, similar to what’s used in automotive manufacturing, but adapted for outdoor use and concrete deposition.

The concrete deposition system consists of:

- A ten-cubic-meter hopper for concrete mix

- A pumping system that maintains consistent pressure

- A deposition nozzle controlled by the robotic arms

- A real-time monitoring system that measures concrete flow rate, temperature, and consistency

The robot prints concrete in layers. Each layer is two centimeters thick and approximately forty centimeters wide. The robot arm moves in a continuous path, depositing concrete in a precise pattern defined by the AI planning system. As it deposits each layer, a separate subsystem integrates steel reinforcement from pre-cut bundles loaded into a magazine on the platform.

The print speed is twelve centimeters per second of linear wall. For a typical house with one hundred twenty linear meters of wall (perimeter plus interior walls), this means printing one layer takes approximately seventeen minutes. A two-point-four-meter-high wall requires one hundred twenty layers, so the total printing time is approximately thirty-four hours for the complete wall structure.

Add in foundation work, roof printing, and repositioning time, and the total robot operation time per house is approximately forty-two hours. With two robots working simultaneously (one doing foundation and walls, one doing roof and details), the house structure is complete in twenty-four to thirty hours.

The robot doesn’t need breaks, doesn’t need supervision beyond monitoring, and works at consistent quality twenty-four hours a day. It doesn’t get tired, doesn’t make measurement errors, and doesn’t argue with the plumber about whose fault it is that the rough-in is wrong.

Operating cost per hour: Electricity (fifteen kilowatts average draw at €0.30 per kilowatt-hour) = €4.50. Concrete materials at consumption rate = €18 per hour. Wear and maintenance amortized = €3 per hour. Total: €25.50 per hour.

Forty-two hours of robot operation = €1,071 per house.

Compare this to traditional construction labor: Approximately eight hundred hours of skilled labor (carpenters, masons, concrete workers, etc.) at €48 per hour average = €38,400.

The robot is ninety-seven percent cheaper than human labor for the core structure.

The Secondary Systems Robot:

After the structure is printed and cured for twenty-four hours, the secondary systems robot arrives. This is a smaller, more agile platform designed for precision work inside the structure.

It has four articulated arms, each equipped with specialized end effectors:

- Arm 1: Drilling and anchoring for electrical and plumbing fixtures

- Arm 2: Cable pulling and wire management

- Arm 3: Pipe fitting and connection

- Arm 4: Inspection and quality control (cameras and sensors)

This robot follows pre-programmed paths through the structure, installing electrical conduit in the channels that were created during the wall printing process. It pulls wires, installs outlet boxes, connects circuits to the main panel. It does the same for plumbing—PEX tubing pulled through floor channels, connected to fixtures, pressure-tested automatically.

The HVAC installation is semi-manual. The heat pump units are too heavy and awkwardly shaped for the current robots to handle efficiently, so a two-person human crew positions and mounts them. But the robot handles all the refrigerant line routing and electrical connections.

Total time for systems installation: sixteen hours with the robot plus eight hours of human oversight and heavy-component placement.

Cost: Robot operation = €16 x €15/hour = €240. Human labor = €8 hours x 2 workers x €30/hour = €480. Total = €720.

Compare to traditional systems installation: Electricians (eighty hours), plumbers (sixty hours), HVAC specialists (forty hours), total one hundred eighty hours at €48/hour average = €8,640.

The robot plus minimal human labor is ninety-two percent cheaper.

The Chinese Manufacturing Partnership:

Guerrilla Construction doesn’t manufacture the robots or the prefab components themselves. They’re a construction company, not a manufacturing company. Instead, they’ve formed partnerships with Chinese manufacturers who produce everything to specification.

The robots are manufactured by Shenzhen Automation Systems, a company that normally produces factory automation equipment for electronics manufacturing. They designed the construction robots to Guerrilla Construction’s specifications in a six-month development process. Development cost: four hundred thousand euros, paid by Guerrilla Construction.

The robots are manufactured at a rate of two units per month. Current production has delivered thirty robots over fifteen months. Manufacturing cost per robot: one hundred forty thousand euros. Guerrilla Construction’s ownership cost per robot, including development amortization: one hundred fifty-three thousand euros.

The prefab components—bathroom pods, kitchen units, window and door frames—are manufactured by various companies in Guangdong province. These are standard Chinese manufacturers who normally produce for domestic construction or export to developing markets. Guerrilla Construction simply placed large orders and signed multi-year contracts guaranteeing volume.

This is the economic power of standardization. When you order five hundred identical bathroom pods per year, you become a significant customer. The manufacturer gives you priority production, quality attention, and aggressive pricing. They optimize their production line for your specific product. Their costs go down, and they pass some of that savings to you to maintain the relationship.

The New Insurance Model:

Traditional Dutch home insurance is provided by large insurers (Centraal Beheer, AEGON, etc.) who price premiums based on construction type, location, age of building, and historical claims data.

New construction typically gets favorable rates because there’s less risk of structural failure or systems breakdown. But insurers are conservative about non-traditional construction. When the first Guerrilla Construction buyers tried to get insurance, they were quoted premiums of fourteen hundred to eighteen hundred euros per year—twice the normal rate—because insurers classified these as “experimental construction.”

Guerrilla Construction solved this by creating their own insurance mutual in partnership with a Malta-based underwriter called Meridian Assurance. Here’s how it works:

All Guerrilla Construction homeowners are required to participate in the mutual. They pay eight hundred euros per year. This money goes into a pooled fund. The fund pays out claims for structural damage, system failures, or other insurable events. Meridian Assurance provides reinsurance—they cover claims above certain thresholds and catastrophic events.

After three years of operation and three hundred forty houses, the claims history is remarkably good. Total claims paid: forty-one thousand euros across three years. This includes:

- Three heat pump failures (covered under warranty, but insurance paid for temporary heating): €6,000

- One roof leak (manufacturing defect in sealant): €2,800

- Minor cracking in two houses (aesthetic issue, not structural): €4,200

- Various small claims (broken windows, door hardware failures, etc.): €28,000

Total claims: €41,000. Total premiums collected: €816,000 (€800/year x 340 houses x 3 years). Claims ratio: 5.0 percent.

Compare this to traditional residential insurance, which typically runs at a forty to sixty percent claims ratio. Guerrilla Construction houses are generating dramatically fewer claims because:

- New construction means no aging systems

- No gas connections means no gas leak/explosion risk

- Over-engineered structure means minimal settling or cracking

- Prefab components have warranties and are replaced rather than repaired

- Waterproofing is excellent due to monolithic construction

The mutual is profitable even at eight hundred euros per year. In fact, Guerrilla Construction is discussing reducing premiums to six hundred euros per year starting in year four.

This is insurance doing what insurance is supposed to do: Pool risk among similar participants and price premiums based on actual risk rather than market power and information asymmetry.

The New Banking Model:

Guerrilla Construction explicitly avoids mortgage financing. They’re trying to help people own houses, not sell them mortgages. But not everyone has twenty-eight thousand euros in cash, even if they’re selling an existing property.

Solution: Peer-to-peer housing bonds.

Here’s the model: Guerrilla Construction operates a platform where individuals can invest in housing bonds. Minimum investment: one thousand euros. Term: five years. Interest rate: four point five percent per annum.

The bonds are used to finance house construction for buyers who need financing. A buyer who can pay fifteen thousand euros cash can borrow thirteen thousand euros through the bond platform. The loan is secured by the house and land. Loan term: five years, no early payment penalty.

The buyer’s monthly payment: approximately two hundred thirty-four euros (principal and interest on a thirteen thousand euro loan at five percent over five years). This is compared to what a mortgage on a two hundred fifty thousand euro house would cost: roughly one thousand three hundred euros per month.

After five years, the loan is paid off and the buyer owns the house outright.

From the investor perspective: four point five percent annual return is attractive in an environment where savings accounts pay two point eight percent. The default risk is low—the loan-to-value ratio is never more than sixty percent, and even if a buyer defaults, the house and land can be sold to recover the loan.

Actual default rate after three years: Zero. Not zero percent—literally zero defaults. Every buyer has kept up payments.

This shouldn’t be surprising. When your monthly housing cost drops from fourteen hundred euros to two hundred thirty-four euros, you have enormous financial breathing room. Missing a payment would require catastrophic financial circumstances.

The bond platform has raised eight point two million euros from four hundred seventy investors. This has financed partial loans for one hundred forty houses. The platform is on track to be self-sustaining—as early loans are repaid, that capital is recycled into new loans.

Guerrilla Construction takes a one percent annual administration fee on the loan principal. This covers platform operation costs and provides a small profit margin. On eight point two million in outstanding loans, that’s eighty-two thousand euros per year in revenue for Guerrilla Construction from the financial side of the business.

The Legal Defense Infrastructure:

Guerrilla Construction has three law firms on retainer:

- Velsing & Partners (Rotterdam): Specialists in administrative law and gemeente relations

- Holtzman Advocaten (Amsterdam): Construction law and contract disputes

- Van Der Meer Legal (Den Haag): Constitutional and European law

Annual retainer across all three firms: two hundred forty thousand euros.

These firms handle:

- Permit applications and appeals

- Dispute resolution with gemeentes

- Defense against lawsuits from competitors

- Contract negotiations with suppliers

- Buyer contract templates and legal support

The legal strategy is aggressive: Always challenge, never settle early, document everything, and be prepared to litigate to the highest courts if necessary.

This might seem expensive—two hundred forty thousand euros per year—but at six hundred houses per year, it’s four hundred euros per house. And the legal infrastructure provides value far beyond just defense. It actively shapes regulatory interpretation, creates favorable precedents, and signals to gemeentes that Guerrilla Construction will not be intimidated.

One partner at Velsing, Daan Hendriks, has become the public face of Guerrilla Construction’s legal efforts. He’s argued twelve cases before administrative courts, winning nine, partially winning two, and losing one. The loss was on procedural grounds and didn’t set adverse precedent.

Daan is also the person who prepared the European Court of Human Rights brief that’s ready to file if Dutch courts ultimately rule against Guerrilla Construction’s right to exist. The brief argues that access to affordable housing is a fundamental right under Article Eight (right to family life) and that Dutch regulatory barriers constitute an unjustified interference with that right.

It’s not clear if this argument would win at the ECHR, but the mere existence of the brief—and Guerrilla Construction’s willingness to pursue it—has made several gemeentes more willing to negotiate rather than litigate.

The Power of Stonewalling:

Here’s a legal strategy that doesn’t get discussed often in polite company: Sometimes the best defense is just refusing to comply until forced by a final court order.

Gemeentes issue violation notices. Guerrilla Construction acknowledges receipt and files appeals. The appeals take six months to adjudicate. During those six months, families live in the houses. When the gemeente wins the appeal, Guerrilla Construction files a further appeal to a higher administrative court. This takes another eight months.

During this time—fourteen months total—the families are established. Children are enrolled in schools. Parents are commuting to work. The houses have addresses, utility connections, postal service. They exist in every practical sense.

When the case finally reaches final adjudication, the judge faces a choice: Order demolition of occupied homes, or find some legal basis to permit them to remain.

Judges, it turns out, are very reluctant to order demolition of occupied homes where children live, especially when the homes are demonstrably safe and the violations are purely procedural.

In eight cases where gemeentes have pushed litigation to final judgment, Guerrilla Construction has “lost” five times—meaning the court ruled that construction without permits was improper. But in four of those five cases, the remedy was fines and retroactive permit requirements, not demolition. In only one case was demolition ordered, and that case is under appeal to the Council of State and has been stayed pending review.

The time delay is the weapon. By the time legal processes resolve, the houses are facts on the ground that are politically and practically difficult to remove.

This is not technically illegal. Guerrilla Construction follows all court orders once they become final. They pay all fines assessed. They comply with all remediation requirements. They just use every available legal avenue to delay final judgment as long as possible, during which time the houses become increasingly difficult to uproot.

The Result: A System That Scales:

All of these pieces—AI planning, standardization, Chinese manufacturing, robotics, alternative insurance, peer-to-peer finance, and aggressive legal defense—combine into a system that can scale.

Guerrilla Construction built six houses in May, eighteen in June, thirty-six in July, fifty-four in August, and is on track for seventy-two in September. This is exponential growth enabled by:

- Adding more robots (currently thirty, expanding to fifty by year-end)

- Optimizing the supply chain (reducing lead times from order to delivery)

- Pre-negotiating with cooperative gemeentes (eight gemeentes now have pre-approved sites)

- Building the financial platform (more investor capital = more buyer financing)

At current growth rates, Guerrilla Construction will build one thousand houses in year two. At one thousand houses per year, the economics improve further—equipment amortization drops, bulk purchasing power increases, legal costs per house decrease.

The model isn’t just disrupting construction. It’s proving that housing can be radically cheaper and that the entire existing system is built on artificial scarcity and extraction rather than genuine constraints.

And the traditional construction industry is watching this happen with growing horror, which brings us to the lawsuit.

CHAPTER 4: THE COUNTERATTACK

Narrative: When the System Fights Back

The lawsuit is filed in September by a consortium called Stichting Bouwkwaliteit Nederland (Foundation for Dutch Construction Quality), which sounds like a public interest organization but is actually funded by five of the largest construction companies in the Netherlands: BAM, VolkerWessels, Dura Vermeer, Van Wijnen, and Heijmans.

The legal theory is creative. They’re not suing Guerrilla Construction directly—that would look bad, big companies attacking a disruptor trying to make housing affordable. Instead, they’re suing twelve gemeentes that approved Guerrilla Construction permits, claiming these gemeentes violated proper administrative procedures and created “dangerous precedents that undermine building safety standards and market stability.”

The lawsuit seeks:

- Revocation of all permits granted to Guerrilla Construction

- Injunctions preventing further permit approvals

- Financial penalties against gemeentes that approved permits

- Orders requiring comprehensive safety reviews of all existing Guerrilla Construction homes

The press release emphasizes safety concerns and regulatory integrity. It doesn’t mention that Guerrilla Construction houses have passed every structural inspection or that the real concern is market disruption.

But the lawsuit is just one front in a broader counterattack.

Amersfoort, October

Hendrik and Marieke van Dijk live in a traditional three-bedroom semi-detached house in a neighborhood called Vathorst. They bought it in 2019 for three hundred ninety thousand euros with a mortgage at 2.3 percent—one of the last great deals before interest rates rose. The house is now worth approximately four hundred twenty thousand euros according to their most recent valuation. Or was worth that.

In July, a Guerrilla Construction development went up two kilometers away. Fifteen houses, printed in four days on former farmland. The houses sold for twenty-eight to thirty-four thousand euros.

Hendrik first heard about it at a neighborhood barbecue. “Did you see those weird black houses over on Eikenlaan?” someone said. “They look like something from outer space. Built in a week. Cost nothing.”

He drove over to look. The houses were strange—smooth, curved, definitely not traditional Dutch architecture. But they looked solid. There were families living in them, kids playing, normal life.

Two months later, Hendrik and Marieke decided to sell their house. They’re both in their early fifties, the kids are grown, and they want to downsize and move closer to the coast. They listed the house at four hundred twenty-nine thousand euros—a slight premium for the neighborhood, but justified by recent renovations.

The house sits on the market for six weeks with only two viewings. Finally, their real estate agent, a woman named Sandra, comes over for a difficult conversation.

“The market has shifted,” Sandra says carefully. “Vathorst is… experiencing pricing pressure.”

“What does that mean?” Marieke asks.

“It means buyers are aware of the Guerrilla Construction development. They’re asking questions. Why should they pay four hundred thousand euros for a house here when they can buy land and a new house for under one hundred thousand total?”

“Because our house is bigger, nicer, in an established neighborhood,” Hendrik says, feeling defensive.

“I understand. But the math is difficult for buyers to overcome. Your monthly mortgage cost at current rates would be around twenty-two hundred euros. A Guerrilla Construction house has no mortgage cost—just utilities and insurance, maybe three hundred euros per month. That’s a difference of nineteen hundred euros per month.”

“So what are you saying?”

Sandra takes a breath. “I’m saying we need to rethink pricing. I’d recommend listing at three hundred seventy-nine thousand.”

“That’s a fifty-thousand-euro loss from where we expected!” Marieke says.

“I know. But I have five other listings in Vathorst right now, and they’re all sitting. The market here is effectively frozen. People are waiting to see what happens with Guerrilla Construction. If they expand, prices could drop further. If they get shut down, prices will recover. But right now, buyers are paralyzed.”

Hendrik and Marieke don’t reduce their price that day, but three weeks later, after another open house with zero attendees, they drop to three hundred seventy-nine thousand. A month after that, they accept an offer of three hundred fifty-five thousand—thirty-five thousand euros less than the valuation, sixty-five thousand less than they’d hoped.

Hendrik is angry. Not at Guerrilla Construction exactly, but at the situation. “We worked for this house,” he says to Marieke the day they accept the offer. “We saved for years for the down payment. We’ve been paying the mortgage for five years. And now someone can just buy a house for thirty thousand euros and we’re supposed to compete with that?”

Marieke doesn’t have an answer.

Two weeks later, Hendrik attends a community meeting organized by the Vathorst homeowners’ association. The topic: “Protecting Property Values in the Face of Disruptive Development.”

Forty-seven people attend. A representative from Stichting Bouwkwaliteit Nederland gives a presentation about the lawsuit and the importance of maintaining building standards. A local council member talks about the gemeente’s commitment to orderly development. A real estate market analyst presents data showing that neighborhoods within three kilometers of Guerrilla Construction developments have experienced 6.2 percent price declines on average.

“This isn’t just about one development,” the analyst says. “If this model spreads, traditional housing values across the Netherlands could decline by fifteen to twenty-five percent. That’s a loss of two hundred to three hundred billion euros in homeowner equity.”

There’s anger in the room. These are people who followed the rules, who saved and borrowed and paid their mortgages, who invested their wealth in real estate because they were told it was safe, and now they’re watching that wealth evaporate because someone invented a cheaper way to build houses.

One man stands up. “Can we sue Guerrilla Construction? For damages?”

The lawyer from Stichting Bouwkwaliteit shakes his head. “Unlikely to succeed. They’re not doing anything illegal. They’re just offering a competing product at a lower price. That’s capitalism.”

“Then what can we do?”

“Support the political process. Make noise. Let your gemeente representatives know this matters to you. The national government is paying attention. There will be legislation.”

After the meeting, Hendrik signs a petition calling for stricter regulation of “experimental construction methods.” So do thirty-nine other attendees.

They’re not bad people. They’re not trying to keep young families out of housing. They’re just trying to protect what they’ve built, the equity they’ve accumulated, the nest egg they were counting on for retirement.

But their interests are now in direct conflict with anyone trying to buy their first home.

Rotterdam, November

Karen de Boer is a mortgage advisor at ING Bank. She’s been in this job for eleven years, and she’s good at it. She helps people understand loan options, runs the numbers, gets them approved. On average, she processes eight to twelve mortgage applications per month.

In November, she processes three.

“What’s happening?” her manager asks in their monthly review.

“Guerrilla Construction,” Karen says simply.

“Explain.”