To have a tourist destination on the surface of Venus had been proposed more than once, and each time it was dismissed with a kind of exhausted finality. The planet was not merely hostile; it was methodically, patiently lethal. Yes, sizeable structures had been landed there, and yes, geological samples had been retrieved, but only at grotesque cost. The machines that accomplished those feats were built to endure for hours at most, occasionally days, and even then they died nobly in the attempt. There was no credible pathway to allow humans to descend to the surface safely, comfortably, and for any duration that justified the staggering expense.

Then the Solar Sheiks of Mercury entered the picture. They possessed the particular variety of wealth that does not seek return on investment so much as exemption from limitation. They did not want a research outpost, nor a symbolic flag planted in basalt. They wanted windows. They wanted a restaurant. They wanted suites with climate control and piano music and the kind of lighting that flatters both the diner and the apocalypse beyond the glass. They wanted an express elevator, safe landing facilities, and the reassurance that one could arrive, dine, and depart without feeling as though one had flirted with extinction. When engineers explained that the surface pressure was ninety-two bar and the temperature hovered near four hundred and seventy degrees Celsius, the Sheiks listened politely and then asked how much it would cost to make those numbers irrelevant.

Money was applied to the problem in quantities so large that they ceased to function as deterrents. Entire disciplines were retooled around a single question: how does one create a pocket of civility inside the most violent atmospheric regime in the inner Solar System? Hubris was certainly present, but so was patience, and eventually patience funded ingenuity long enough for it to mature. What had been declared impossible was not refuted in a single breakthrough but eroded, layer by layer, by systems that redistributed stress, compartmentalized risk, and treated Venus not as an enemy to be conquered but as a gradient to be negotiated.

They succeeded, though not in the way early dreamers imagined. The surface was not tamed; it was insulated from, buffered against, and very carefully observed. What was constructed was not a hotel dropped onto hell, but an engineered sequence of environments, each one slightly less hostile than the one below it, until at last a room could exist where a person might sit, order a meal, and look outward through armor thick enough to make the word “window” feel almost mischievous.

I will not describe how it was built, because the construction process belongs to a technological era that would sound like mysticism to someone in 2026. You could memorize the terminology and still miss the logic that made it routine. Instead, I will describe what was ultimately assembled, in simple structural diagrams and in conceptual layers, so that the architecture itself becomes legible even if the fabrication methods remain politely out of reach. I will proceed step by step, not because the system is simple, but because clarity is a courtesy.

Part Two — The Sponsor

Week One did not fail because of physics. It failed because of tone.

The design team had assembled in what the sponsor insisted on calling the Aurora Chamber, a crescent-shaped conference hall suspended inside a rotating Mercurian solar array. Outside the transparent shielding, the Sun glared at an angle that would have cooked a lesser civilization. Inside, the air was cool, filtered, and faintly scented with something engineered to calm primates under fiscal stress. It was not working.

On the central table hovered a volumetric projection of Venus: yellow-white cloud bands turning slowly, radar topography ghosted faintly beneath. The surface shimmered in false color overlays—temperature gradients, sulfur concentration indices, shear stress models. Every layer was hostile. Every parameter was red.

Dr. Halvorsen, team lead, had already said “untenable” four times.

“We have exhausted aerostat options,” she said, tapping through the first slate of models. “Free-floating habitats at fifty-five kilometers are viable. Tethered platforms are viable. Surface tourism is not viable. There is no safe transport pathway to the ground that satisfies your stated service demands.”

The service demands had been delivered in a document titled Experience Profile: Level Dante. It contained phrases like uninterrupted observation glazing, fine dining capacity for eighty, secure elevator transit under two hours, and guaranteed atmospheric isolation events below one per century.

Halvorsen rotated the projection to reveal surface pressure. Ninety-two bar pulsed in red.

“The pressure envelope alone,” she continued, “requires deep-sea analog structural ratings. At four hundred and sixty degrees Celsius continuous ambient. Corrosion from sulfur compounds. Wind shear increasing with altitude. Lightning probability in upper bands. We can land probes. We cannot build a hospitality venue.”

Across the table sat the sponsor. He was not large. He did not need to be. The Solar Sheik of the Inner Concourse wore no insignia except a narrow band of photonic gold at his wrist. It refracted the chamber light like a small captive star.

He watched the projections as if they were a slow art installation.

“And the cost?” he asked.

Halvorsen hesitated. “Infinite, in practical terms.”

He smiled faintly. “There is no such number.”

That was the moment the room shifted from engineering problem to political event.

The team had arrived prepared to propose scaled-back alternatives: high-altitude observatories, immersive surface simulations, telepresence suites. They had expected negotiation. What they encountered instead was appetite.

The junior systems analyst, Kade Iqbal, had not been expected to speak. He was three months out of graduate orbital mechanics and had been assigned to atmospheric gradient modeling. He had spent the week feeding worst-case parameters into the firm’s architectural synthesis engine, a machine colloquially referred to as the Churn.

The Churn did not care about plausibility. It optimized against constraint sets. Give it compressive strength, density, creep coefficients, corrosion allowances, and it would extrude geometry.

Most of its outputs were absurd.

Kade had not intended to show any of them.

Halvorsen concluded her summary with the phrase, “There is no pathway.”

The sponsor leaned back. “I require a pathway.”

Silence thickened. The volumetric Venus continued to rotate, indifferent.

Halvorsen folded her hands. “Then we must redefine the problem.”

Kade’s display flickered at his wrist. He had queued a file without realizing he had done so. A ghosted wireframe rose beside the planetary projection.

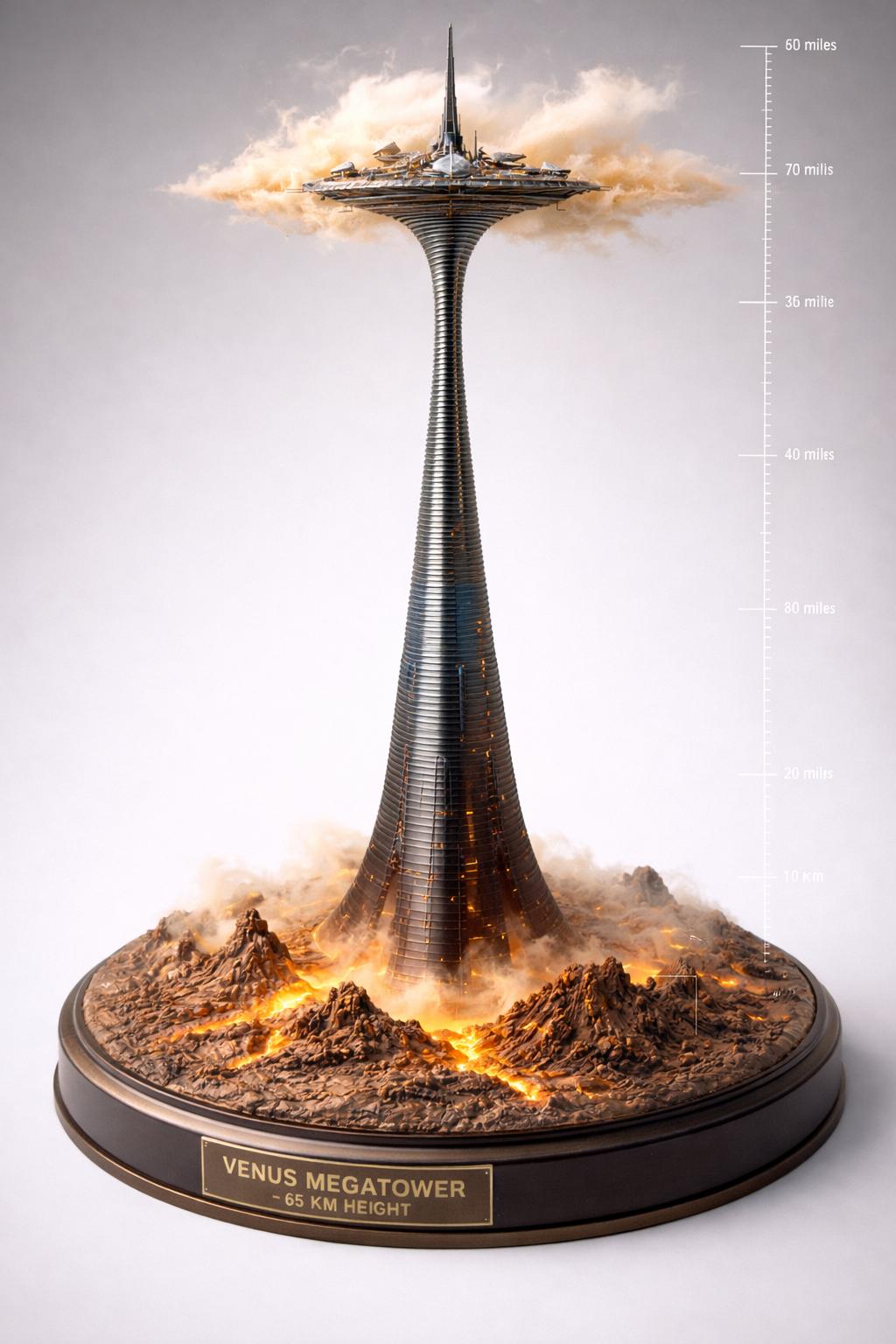

It was tall. Impossibly tall. A narrow spine extending from surface to cloud band. Tapered. Segmented. Ridged.

Halvorsen saw it first.

“Kade,” she said sharply, “clear that.”

He did not. His throat felt dry but his voice came out level.

“The Churn generated it when I forced a surface-to-cloud service constraint with zero external tether reliance,” he said. “I assumed a compressive structure anchored to bedrock with staged buoyancy transitions.”

Someone at the table laughed once, softly, as if at a funeral joke.

The projection refined itself. The base flared slightly to distribute load into subsurface strata. Above that, the structure narrowed into a long, logarithmic taper. Horizontal ridgings marked module boundaries, each corresponding to a shift in atmospheric density. At approximately sixty-five kilometers, a platform ringed the spine like a halo.

The sponsor leaned forward.

Halvorsen closed her eyes briefly. “This is not a proposal,” she said. “It is a stress test.”

Kade nodded. “Yes.”

“And the result of the stress test?”

He swallowed. “The result is that, given materials at the upper bound of projected ceramic-metal composites, and assuming segmented expansion joints every three hundred meters, and assuming active thermal management, the Churn did not return structural failure under static load.”

Silence again.

Wind shear vectors appeared along the spine. The structure flexed subtly in simulation, absorbing lateral load. Atmospheric buoyancy coefficients changed with height, altering effective weight. The ridgings thickened in zones of peak bending moment.

Halvorsen spoke through clenched control. “The Churn does not model construction feasibility. It does not model supply chain. It does not model economic sanity.”

“It models whether the thing falls over,” Kade said quietly.

The sponsor’s gaze had not left the projection.

“Explain,” he said.

Kade gestured, and the view cut to a cross-section. Hollow core. Vacuum insulation annulus. Inner transit tube. External exoskeletal lattice. Anchoring pylons descending into basalt layers beneath ancient lava plains.

“The base,” he said, “would embed into stable bedrock identified via deep-penetration seismics. Load is distributed along the embedded length. The structure tapers to maintain compressive stress within material limits. Horizontal ridgings correspond to transition bands where atmospheric density changes significantly. They act as both structural stiffeners and aerodynamic disruptors.”

Halvorsen’s voice was ice. “It is a tower.”

“Yes,” Kade said.

The word hung there like profanity.

The sponsor smiled more fully now.

“A tower,” he repeated. “On Venus.”

Halvorsen found her footing. “It would be sixty-five kilometers tall. Subject to continuous thermal load from the surface. Exposed to super-rotational wind regimes aloft. Lightning interaction in upper layers. Chemical attack along the entire envelope. The cooling requirement alone would be on the order of a small stellar output.”

“Then we would cool it,” the sponsor said mildly.

“It is absurd,” she replied.

The sponsor tilted his head. “But why not? I like it.”

The room went very quiet.

There are moments in high-budget engineering when the collective nervous system of a team recognizes that it has crossed from optimization into myth-making. This was one of them.

Halvorsen felt something between vertigo and fury. “Because liking it is not a parameter,” she said.

“It is for me,” he replied.

He stood and approached the projection. His hand passed through the upper platform ring. The simulation adjusted scale to maintain proportion against the planetary globe.

“How much?” he asked.

Halvorsen blinked. “For what?”

“For the next phase. To determine whether this tower, as you call it, can be made real.”

Kade stared at the floor.

Halvorsen calculated reflexively. Materials research. Deep Venusian geotechnical surveys. Atmospheric modeling at resolution orders above current baselines. Active cooling loop development. Lightning mitigation systems. Elevator transit design under ninety-two bar gradient.

The numbers that assembled in her mind were not estimates. They were insults.

“Too much,” she said.

He turned toward her. “There is no such number.”

The Churn continued to refine the model. In one inset, a stress distribution heat map glowed from red at the base to cool blues aloft. In another, dynamic sway amplitude remained within tolerances under projected wind shear. Atmospheric buoyancy offset a fraction of compressive load, barely perceptible but present.

“It cannot be built with current industrial capacity,” Halvorsen said.

“Then we expand capacity.”

“It would require dedicated launch lanes. Materials not yet certified at those temperatures. Years of planetary-scale logistics.”

“You have seen what we have done to reach Sedna. They said 300 years. We did it it fifty. Of course this can be done.”

The sponsor’s band of photonic gold caught the light and scattered it across the table like a spectrum.

“Also, I asked for windows,” he said. “And a restaurant. And safe descent. You have shown me a path.”

Halvorsen felt something fracture internally—not hope, not resignation, but the recognition that refusal would not end the conversation. It would merely remove her from it.

Around the table, senior engineers avoided eye contact. One of them began to laugh under his breath, then stopped abruptly.

Kade, the junior analyst, stood very still. He had not intended to start this.

The sponsor looked back at him. “What is your name?”

“Kade Iqbal.”

“Mr. Iqbal,” the sponsor said, “how much do you need?”

Kade opened his mouth, then closed it.

Halvorsen answered for him.

“An obscene amount,” she said. “Half Sedna.”

The sponsor nodded once. “Approved.”

There are approvals that feel like victories. This did not. It felt like gravity shifting direction.

Halvorsen sat down slowly.

The projection of the tower remained suspended between them, thin and implausible, ridged at intervals like the spine of some engineered leviathan reaching from lava plains to luminous cloud.

“Prepare a formal metrics review,” the sponsor said. “I want stress tolerances, material envelopes, cooling load requirements, wind shear simulations, corrosion projections. I want to know where it breaks.”

He paused.

“And then I want to know how we prevent it from breaking. And longterm I would like to look at … synergy. Because this approach… actually unlocks the surface of Venus. Industrially.”

He left the chamber without further ceremony.

The door sealed behind him with a soft hiss.

For several seconds, no one spoke.

Then one of the structural analysts whispered, “We’re actually doing this.”

Halvorsen stared at the model. The base embedded into basalt. The midsection narrowing through dense atmosphere. The upper platform hovering in relative temperance. It was elegant. It was obscene.

“It appears,” she said quietly, “that we are.”

Around the table, the team did not cheer. They did not celebrate. They began, almost reflexively, to pull up stress models, to annotate load paths, to argue about creep coefficients and lightning grounding and sulfuric deposition rates.

The nervous breakdown did not come as screaming. It came as spreadsheets.

They would look at the metrics next.

3. The Metrics.

a. Height and Gravity

Height above surface: ~65 km

Venus gravity: 8.87 m/s² (about 0.9 Earth gravity)

That means gravity is not your primary enemy. Heat is. Pressure is. Time is.

The tower is tall, but not orbital. We are firmly in compressive-structure territory, not space-elevator territory.

b. Self-Weight Compression

For a vertical structure, base compressive stress from its own weight is roughly:

σ≈ρgh

Where:

-

ρ = material density

-

g = Venus gravity

-

h = height

If the structure were solid and uniform (it won’t be, but as a baseline):

For a material density of 3,000 kg/m³ (advanced ceramic composite range):

σ≈3000×8.87×65,000≈1.73 GPa\sigma ≈ 3000 × 8.87 × 65,000 ≈ 1.73 \text{ GPa}

That’s the compressive stress at the very base from self-weight alone.

That number is not absurd if you assume:

-

ultra-high compressive strength composite

-

carefully optimized taper

-

hollow core

With tapering, that stress drops significantly because upper sections weigh less.

Conclusion: compressive self-weight is brutal but not impossible with frontier materials.

c. Thermal Load

Surface temperature: ~460–470°C

At 60 km: ~0–30°C

That is a ~430°C gradient across the height.

Unmanaged, this causes:

-

differential expansion

-

bending stress

-

microfracture propagation

Linear thermal expansion for advanced composites may be ~5–10×10⁻⁶ /K.

Over 430 K difference:

ΔL/L≈0.002–0.004

For 65,000 m height:

ΔL≈130–260 meters

That is catastrophic if the structure is monolithic.

Therefore:

-

It must be segmented.

-

Expansion joints every few hundred meters.

-

Modules thermally buffered.

Cooling is not optional. It is structural.

d. Atmospheric Pressure

Surface pressure: ~9.2 MPa (92 bar)

If Level Dante is pressure-equalized, external pressure does not crush the structure globally. However:

-

Any cavity must resist differential pressure.

-

Elevator shaft transitions must be staged.

-

Seals become life-critical systems.

Pressure is a local engineering problem, not a global structural one — unless you insist on large unbalanced voids.

e. Wind Shear and Dynamic Load

Surface winds: slow but dense air.

Upper atmosphere (~40–65 km): faster winds, lower density.

Dynamic pressure:

q=½ρv2

Even if density drops aloft, wind speeds increase. The critical issue is not mean drag. It is:

-

oscillation

-

vortex shedding

-

resonance

For a 65 km cantilever, even millimeter oscillations at base become meter-scale at top.

The tower must:

-

have tuned damping modules

-

incorporate aerodynamic shaping (wing-like cross-section helps)

-

avoid coherent vortex lock-in frequencies

The horizontal ridgings you requested? They actually make sense. They:

-

break up vortex formation

-

increase torsional stiffness

-

mark structural transition zones

f. Atmospheric Buoyancy

Venus near-surface density: ~65 kg/m³

At altitude: decreases significantly

Buoyant force per cubic meter:

Fb=ρg

At surface:

≈65×8.87≈576N/m

That offsets roughly 60 kg per cubic meter of structural mass.

It is not transformative — but over 65 km of volume, it meaningfully reduces effective compressive load.

This is one reason the Churn did not immediately reject the concept.

The tower is not entirely “weighing itself down.” It is partially submerged in a dense gaseous ocean.

g. Bedrock and Anchoring

Basalt compressive strength: potentially 100–300 MPa depending on integrity.

But at 460°C sustained, creep matters.

The anchor must:

-

distribute load along embedded length

-

use frictional engagement

-

avoid concentrating stress at a single interface

Embedding depth of several kilometers is not overkill. It is stabilizing.

If anchored properly, the base does not act like a foot — it acts like a root system.

h. Corrosion

Continuous exposure to:

-

CO₂ at high pressure

-

sulfur compounds

-

possible upper-atmospheric acid droplets

Outer shell must be:

-

corrosion-resistant composite

-

layered with sacrificial coatings

-

periodically maintained

Surface degradation cannot be allowed to reach structural core.

This becomes a lifecycle cost issue, not an initial viability issue.

i. Lightning and Electrical Effects

The tower spans atmospheric charge gradients.

It will become a preferential discharge pathway.

Therefore:

-

integrated conductive spine

-

controlled grounding to bedrock

-

segmented electrical isolation to prevent cascading failure

Without this, the first major discharge event could induce thermal shock.

j. Elevator Transit

65 km vertical transit under changing pressure regimes.

This requires:

-

staged pressure locks

-

magnetic or cable-less lift system

-

dynamic balancing for tower sway

The elevator is not structurally dominant — but operationally dominant.

k. Cooling Load

Surface modules must reject continuous heat inflow.

Heat will be:

-

conducted inward

-

radiatively absorbed

-

mechanically generated

Heat must be pumped upward to ~55–65 km and rejected into cooler atmospheric band.

This likely requires:

-

multi-loop coolant system

-

massive heat exchangers at altitude

-

external wind-assisted convection

Cooling power demand is enormous.

Fortunately, the upper atmosphere is windy.

Summary

The metrics do not say “impossible.”

They say:

-

brutally material-dependent

-

thermally complex

-

dynamically sensitive

-

financially deranged

The governing constraints are:

-

Compressive strength vs density ratio

-

Thermal expansion management

-

Wind-induced oscillation control

-

Long-term creep in both structure and bedrock

Nothing in the baseline equations violates physics.

What violates comfort is scale.

And that is where the sponsor smiles.

4. It’s there. It was Built. You can visit. You can’t Afford to.

I will not tell you how long it took to build. I will not tell you what decade it was begun, nor the year in which the first elevator capsule descended toward Level Dante with paying guests inside. Time, in this case, is a revealing detail. It triangulates too many other capacities. It exposes the maturity of propulsion, the normalization of long-horizon capital, the quiet acceptance that fifty years of travel to Sedna is considered “fast.” If I told you when it happened, you would begin solving the wrong equation.

The Solar Sheiks did not operate inside the temporal psychology of early twenty-first century civilization. Their wealth was not measured in quarterly returns but in the ability to sustain projects that outlived their initiators. When one has already committed to a settlement trajectory toward Sedna with a fifty-year transit time—considered efficient, even elegant—the notion of a multi-decade construction effort closer to home does not register as daunting. It registers as Tuesday.

But to specify the duration would collapse the frame. If I say it took twelve years, you imagine aggressive industrial mobilization. If I say forty, you imagine generational continuity and patient iteration. If I say eighty, you infer institutional transformation. Each number carries implications about manufacturing throughput, material science, political stability, and the tolerance for deferred gratification. The reader begins to reverse-engineer the civilization instead of the structure.

That is not the point.

Likewise, I will not describe how it was built. Construction methods reveal capability in ways that static geometry does not. If I tell you that modules were assembled in orbit and lowered through the atmosphere in staged descent cradles, you infer atmospheric braking mastery. If I tell you they were extruded in situ from bedrock upward, you infer molecular manufacturing at industrial scale. If I mention self-healing composites or autonomous swarm assemblers operating under ninety-two bar pressure, you begin placing the story on a timeline whether I want you to or not.

So we will leave that blank.

What matters is not the choreography of cranes and robots but the fact of persistence. The project survived feasibility studies, survived materials failures, survived early anchor tests that cracked and had to be redesigned. It endured cooling loop redesigns, corrosion surprises, and at least one near-catastrophic miscalculation in dynamic wind coupling. It persisted through budget expansions so large that older economies would have called them delusional. The Solar Sheiks did not retreat when the numbers became obscene. They simply adjusted the ledger.

By refusing to specify when or how, I remove the temptation to treat this as prophecy or retrospective documentary. It is neither. It is an artifact of a civilization that had already normalized the idea that fifty years to Sedna was a brisk commute and that building a sixty-five-kilometer structure through a corrosive, superheated atmosphere was not madness but preference.

The tower exists. That is sufficient.

The dates, the shipyards, the fabrication epochs, the logistics chains that threaded between Mercury and Venus—those are distractions. If you are enlightened, you already suspect the contours of that world. If you are not, the numbers would only confuse you.

5. Landing and Platforming

The shuttle does not roar in. It descends with a kind of arrogant composure, throttling down through layers of gold-white haze as if gravity itself were a subscription service already paid for. From the observation decks of Venustown the arrival looks ceremonial: a vertical needle of polished alloy lowering itself toward a hexagonal pad marked in corporate livery and hazard glyphs so tastefully minimal they might pass for art.

Up close it is procedural.

Magnetic guidance collars engage before touchdown. The landing struts never quite “strike” the surface; they settle into a receiving lattice that clamps, aligns, and pressure-equalizes in one motion. Vapor plumes vent laterally in controlled sheets, not dramatic flame but disciplined thermodynamics. Within ninety seconds the shuttle is no longer a spacecraft but an annexed module, grafted onto the platform’s circulatory system.

Inside, the passengers are already sealed in their descent garments.

The suits are immaculate and faintly iridescent, each tailored to biometric specification and used precisely twice: once for descent, once for ascent. Afterward they are stripped of identity markers, shredded, and returned to the bulk matter stream. The official explanation is hygiene and security. The unofficial one is privacy. No one wants trace fibers from Level Dante clinging to a museum archive. No one wants a genetic whisper from a billionaire brushing up against a forensic curiosity a century later. The suits are anonymity made fabric.

They are not bulky. They are architectural. Thin layers of adaptive insulation, microchannel cooling, and pressure-buffering membranes lie under a sculpted outer shell whose lines echo the tower itself. Each suit carries its own filtered micro-atmosphere during transit between pressure regimes. The grotesquely rich prefer not to “share air” while crossing gradients.

The cabin opens only after triple verification from platform control. A segmented collar mates with the shuttle hatch. Pressure equalizes in stages measured in decimals. The inner door retracts.

There is no rush.

A soft walkway extrudes forward, its surface lit by a muted path of white embedded beneath translucent composite. Platform attendants stand at a respectful distance. Their uniforms are severe and immaculate, corporate insignia reduced to thin metallic lines along the collarbone. They do not bow. They do not smile excessively. Safety is the aesthetic here.

The first tourist steps forward.

Through the helmet visor the clouds are visible beyond the platform’s outer edge, an ocean of luminous vapor stretching to the horizon. The tower spine rises behind them, disappearing upward into structured geometry and downward into atmosphere. The platform feels solid underfoot, and that solidity is the luxury. Every vibration has been damped. Every oscillation tuned. The grotesquely rich do not pay for spectacle alone; they pay for the absence of fear.

Others follow, each suit subtly distinct in cut and tone. Some pause to record a private feed, lenses embedded at the temple capturing the moment for personal archives. No public livestreams are permitted on first arrival. Exclusivity is part of the contract.

Transport modules glide silently to receive them, mag-locked to guide rails integrated into the hexagonal decking. Beyond, strata of color-coded conduits run in disciplined arcs: red for thermal transfer, green for life support, blue for data spine. It is industrial and unapologetic. The machinery is visible on purpose. Transparency is reassurance.

Within minutes the shuttle is empty. The tourists have entered Venustown’s controlled interior, where climate, lighting, and acoustic design soften the transition from interplanetary travel to curated extremity.

Behind them, technicians detach the descent suits from their docking racks. Each garment is scanned, cataloged, and sent down a discreet conveyor into the reclamation system. Privacy, like everything else here, is engineered.

Outside, another shuttle is already descending.

The reception concourse of Venustown™ glows with engineered warmth, a deliberate counterpoint to the hostile immensity beyond the glass. Through the armored transparencies, the cloudscape churns in luminous gold, but inside the lighting is soft, flattering, curated for skin tones and status photography.

They arrive in clusters.

Young heirs and heiresses — sculpted, symmetrical, almost algorithmically beautiful — step from the transit glide-pods in laughter. Their Venus Exosuits® are obscene in both cost and refinement: contoured composite shells trimmed in metallic filaments, micro-vent lattices glowing faintly in coordinated color palettes. The suits are not bulky survival gear; they are fashion statements wrapped around engineering miracles. Deep cobalt with platinum seams. Pearl-white with rose-gold exostructure ribs. Matte black with luminous cyan tracing.

The helmets retract in synchronized arcs, folding back like ceremonial visors. Perfect hair spills free, untouched by humidity, preserved by internal microclimate systems that cost more than early orbital stations.

They are escorted by concierges — that was the word — who move with studied calm. The concierges wear tailored, sharply minimal uniforms in graphite gray, each with a discreet insignia at the collar. Their expressions are precise: welcoming without familiarity, deferential without submission. They speak softly, guiding guests toward biometric scanners and private lift corridors with an efficiency that borders on choreography.

Laughter carries through the concourse. Someone is already recounting the view from descent, gesturing animatedly toward the glass where Venus broods in eternal haze. A pair of guests pause for a shared capture — not a crude selfie, but a carefully framed holo-snap, the tower spine rising behind them like a monumental exclamation mark.

Behind a series of internal glass barriers — pressure and environmental partitions rendered almost invisible — attendants wait with silver trays. The uniforms here are conspicuously theatrical: short, sharply cut skirts in metallic tones, structured jackets with high collars, polished boots. The aesthetic is retro-futurist indulgence, calibrated to flirt with decadence without quite crossing into parody. On the trays: fluted glasses of champagne whose bubbles rise in perfect, lazy spirals, and small mother-of-pearl spoons cradling black caviar harvested from gene-edited sturgeon orbiting somewhere far kinder than Venus.

The guests accept with delighted exaggeration. There is a kind of rehearsed innocence to it — as if they are aware of the absurdity and determined to enjoy it anyway. Their laughter is bright, insulated from the reality that sixty-five kilometers below them the surface remains a pressure-cooked wasteland.

Overhead, corporate insignia shimmer subtly in the architectural lighting, embedded into the hexagonal lattice of the ceiling. Logos are not plastered; they are integrated, glowing faintly in whites and muted golds, reminding everyone who funded this impossible indulgence.

Everything feels safe. That is the real extravagance. The floors do not tremble. The air does not fluctuate. The tower hums at a frequency too low to be unsettling. Even the glass, meters thick and layered with defensive composites, seems delicate only because it wants to be admired.

The grotesquely rich disembark as if arriving at a mountain resort rather than the edge of a planetary inferno. They are giggling, radiant, unbothered.

Venus waits beyond the glass, dull and eternal.

Inside, the party has begun.

The welcome concourse of Venustown was designed to overwhelm gently.

It was circular, vast without being cavernous, and tiered in two sweeping rings of suites that overlooked the central floor like theater balconies. The curvature of the space was intentional. There were no corners in which to feel lost. Everything bent inward toward the dance floor at the center, toward the restaurants and lounge terraces radiating outward in graceful arcs. The floor itself was a mosaic of polished composite stone and embedded light filaments that traced concentric patterns, glowing faintly beneath the feet of arriving guests.

Beyond the outermost ring, towering panes of armored glass rose from floor to ceiling. Through them the Venusian cloudscape drifted in luminous gold and muted ochre, an ocean of vapor extending to a horizon that seemed improbably close and infinitely distant at the same time. The Sun, diffused through high-altitude haze, bathed the concourse in honeyed light that made skin tones warmer, jewels brighter, and champagne almost incandescent.

Guests arriving from the platform were ushered inward by concierges who moved with quiet authority. Some tourists had already shed their exosuits, now clothed in resort attire that balanced effortlessness with calculated opulence. Others lingered in transitional garments, reluctant to abandon the symbolism of having just descended through the atmosphere of Venus.

Above them, the two layers of suites formed a continuous ring of glass-fronted chambers. Inside, silhouettes moved against soft interior lighting. Each suite had its own private balcony that overlooked the central floor, though the railings were nearly invisible, reinforced by transparent composite that could withstand pressure far beyond anything this altitude demanded.

The lower level of the concourse housed the dance floor and main restaurant area. Tables arranged in curved clusters allowed for intimacy without isolation. A grand piano occupied a slightly raised platform, its black lacquer reflecting the shifting light from above. Waitstaff glided between tables with trays of meticulously arranged cuisine, while discreet service drones hovered near the ceiling, nearly silent, adjusting lighting and sound balance in real time.

To one side, leisure areas branched off in layered terraces: a spa with warm mineral baths set into sculpted basins, misting lightly in controlled plumes; a game arcade that blended immersive holo-environments with physical installations; information booths staffed by impeccably trained guides who could schedule excursions, secure reservations, or arrange personalized surface-viewing appointments. Gift shops curved along the outer ring, their displays curated like museum exhibits. Guests did not carry purchases. They selected, confirmed, and watched as items were sealed in smart packaging and routed through delivery systems that would ensure their arrival at homes scattered across Mercury, Earth orbit, or farther still.

At first the light seemed constant, unwavering. But gradually, almost imperceptibly, the windows began to dim.

It was subtle enough that no one noticed the exact moment of transition. The glass did not simply darken; it modulated, filtering wavelengths and shifting tone in calibrated increments. The golden glare softened into amber, then into a deeper, more theatrical hue. The sky beyond the glass lost some of its brilliance, taking on layered shadows that gave the clouds new depth.

A murmur moved through the concourse as guests became aware of the change.

One of the hosts, a tall man in a sharply tailored jacket with the faintest metallic thread woven into the fabric, stepped onto the central platform near the piano. He raised a glass, smiling broadly as the room’s attention turned toward him.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he began, his voice amplified just enough to reach every corner without seeming intrusive, “as you may have noticed, Venustown observes its own rhythm.”

He gestured toward the glass walls.

“The tower is presently anchored in the day hemisphere of Venus. Out there, the Sun is relentless. But we are civilized here.”

A ripple of laughter passed through the guests.

“To acclimatize you properly before your descent tomorrow, we simulate a cycle more familiar to terrestrial sensibilities. You will find the lighting gradually transitioning into evening mode over the next forty minutes. Dinner reservations will align with the simulated sunset.”

The windows continued to dim, revealing greater contrast in the cloud layers. Distant currents became visible, long streaks of vapor drifting across the upper atmosphere like slow rivers.

“It gets a lot wilder when it’s night time on Venus!” the host added with a grin.

This time the laughter was louder, more curious.

“On the night hemisphere, the upper atmosphere becomes electrically expressive. You will see lightning crawling horizontally across cloud bands, illuminating structures that were invisible moments before. The view changes from honeyed serenity to something… operatic.”

He paused just long enough for the word to resonate.

“Tomorrow evening, if your itinerary allows, we recommend booking an observation session during a night pass. The darkened clouds, the distant flashes, the subtle glow of the tower’s own navigation arrays—truly unforgettable.”

The lighting inside the concourse shifted in harmony with the windows. Overhead rings of illumination transitioned from warm daylight tones to cooler twilight hues. The dance floor lights intensified slightly, casting delicate reflections across the polished surface. The piano began to play, a gentle progression that matched the atmosphere’s descent into evening.

Guests drifted toward the railings to watch the sky. Some raised glasses toward the horizon. Others activated personal recording devices, capturing the transition for private archives. The change was gradual enough to soothe, dramatic enough to impress.

As the simulated sunset deepened, the interior of Venustown grew more intimate. The two rings of suites glowed softly, each balcony framed by understated light strips. The spa terraces flickered with candlelike luminance. The information booths dimmed their displays, switching to evening palettes.

Beyond the glass, the Venusian clouds darkened into layers of bronze and charcoal. Far in the distance, faint flickers began to appear—small at first, then branching into silent arcs of lightning that traced patterns across the upper atmosphere.

A collective intake of breath swept the concourse.

Even the grotesquely rich were not immune to awe.

Inside, music swelled. Glasses clinked. Conversations resumed with heightened energy. The day-night cycle of Venustown continued its measured transition, balancing spectacle with comfort.

Tomorrow, some of these guests would descend to Level Dante, to dine beside armored windows while the surface of Venus glowed dull and eternal. Tonight, they acclimatized gently, cradled within a circular sanctuary that bent light and time to its will, offering them the illusion of normality at the edge of the most inhospitable world in the inner Solar System.

No, this is not the actual surface of Venus.

That becomes clear the moment the guests step fully into the atrium of the Foot.

The volcanoes are too theatrical. The lava too obedient. The lightning forks with timing that borders on choreography. The eruptions crest at precisely the right moment to send a tremor through the floor panels and draw a synchronized ripple of nervous laughter from the new arrivals.

It is spectacle.

A 360-degree holo-environment wraps the atrium in curated apocalypse. Vast calderas glow in molten orange. Pyroclastic plumes roll across the horizon in slow, operatic arcs. Rivers of lava snake toward the balcony edges before dissolving into carefully managed light fields. The illusion is immersive enough that several guests instinctively grip the railing as the first tremor passes beneath their shoes.

The floor vibrates—just enough.

Someone laughs too loudly.

A concierge appears at the edge of the descending elevator ramp, smiling with controlled delight.

“Welcome to the Foot,” she says, as the doors iris closed behind the capsule. “You are currently inside our acclimatization envelope. The environment you are seeing is a dramatized rendering of historic Venusian volcanism. Real-time feeds are available in the observatory lounge and restaurant.”

She gestures toward a sweeping stairway that curves downward into the heart of the atrium.

“But first,” she adds lightly, “tradition.”

At the center of the space rises the statue.

Lucifer

Not the grotesque caricature of medieval paranoia, but something older, prouder. A towering figure in dark metallic composite, wings unfurled, one hand raised toward an unseen star. The surface of the statue is brushed bronze with subtle iridescence, catching the flicker of simulated lava light and scattering it in warm tones across the ceiling.

At the base, the hooves.

Polished bright from contact.

Guests move toward it almost shyly at first. The first pair—a young couple still flushed from descent—approach, hands clasped. The woman laughs under her breath.

“This is insane,” she whispers.

“Rub the hooves,” her partner says.

They do.

A faint chime sounds, subtle enough not to embarrass but audible enough to reward the gesture. Somewhere above, a concealed system registers their arrival and logs the ceremonial touch as part of the experience sequence.

More guests follow. Nervous giggles echo beneath the vaulted ceiling as palms brush cool metal. The statue’s base warms slightly where hands gather, micro-heating elements preventing the surface from feeling cold despite the theatrics of surrounding fire.

“Come quickly!” a host calls playfully from the balcony above. “Before the next eruption cycle!”

On cue, a volcano in the holographic horizon detonates in a cascade of glowing debris. The floor trembles again—perfectly calibrated, perfectly safe.

Beyond the atrium, through thick armored glass panels set into the far wall, lies the actual Venus.

There the sky is duller. The lava fields are not choreographed. The air shimmers in oppressive heat. The colors are more muted, more brown than gold.

The real observatory deck waits beyond, along with the restaurant where diners will sit beside multi-layered transparent shielding and watch the authentic surface in silent awe.

But here, in the welcome chamber, the danger is curated.

Engineered.

Amplified.

The guests laugh, eyes wide, breath quickened.

They came for terror wrapped in velvet.

And the Foot understands exactly how much to give.